At Yokohama AikiDojo, Aikido practice is framed around katageiko — a formalized and cooperative method for engaging with the Aikido curriculum. Historically rooted in the transmission of traditional martial forms, katageiko offers a structured pedagogical model, enabling practitioners to systematically transmit and acquire technical proficiency through repetitive, embodied practice (Råman, 2018).

Unlike some martial arts that emphasize solo forms (kata), Aikido is inherently relational, practiced almost exclusively in pairs, devoid of competitive environment, and it embraces a philosophy of cooperative interaction over domination. Thus, while katageiko provides the essential scaffolding (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976) for technical acquisition, it is not by itself sufficient to foster genuine mastery. Two critical dimensions must complete this framework: sensitivity and empathy. These ensure both the effective learning of techniques and the psychological and physical safety of all practitioners.

This article aims to articulate these expectations clearly, ground practice in a firm theoretical framework, in particular the socio-constructivist theories of learning (Vygotsky, 1978; Wertsch, 1991), with some attention given to embodied pedagogy (Sheets-Johnstone, 2011), where learning and knowledge are thought as fundamentally rooted in the body—in movement, sensation, and lived experience—not just in abstract thought or linguistic expression, as well as relational models of skill acquisition (Rogoff, 1990), where learning and development occur through participation in social and cultural activities, rather than being solely internal, individual processes.

In doing so, we aim to cultivate a dōjō culture rooted in mutual respect, continuous growth, embodied inquiry, and compassionate engagement.

Sensitivity and Empathy in Practice

Sensitivity refers to one's ability to feel the effects of one's partner's techniques so that one can learn from it and attempt to replicate the same effects onto others, but it also refers to the impact of one’s own movements on others. Developing this dual awareness requires not only technical competence but also a refined proprioceptive and interoceptive attunement (Fuchs, 2017), cultivated through mindful engagement with one’s own body and the bodies of others, in order to elicit an embodied cognition (Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991).

Empathy is not a purely emotional reaction, but a complex, cognitive-affective skill that can be cultivated through intentional practice (Decety & Jackson, 2004). In the context of Aikido practice, empathy involves an "empathic imagination" (Gallagher, 2005), which is the capacity to inhabit the other’s experience and modulate one’s further actions accordingly.

A personal note: As someone relatively tall and large by Japanese standards, I discovered over time that even my neutral posture could unintentionally trigger apprehension in my partners. It took a willingness to listen to their feedback—and an effort to internalize it—to realize that softening my stance, modulating my demeanor, or even smile occasionally could significantly diffuse unnecessary tension. Similarly, I had to accept that what I perceive as soft, relaxed practice may still feel heavy or intense to others. This gap in perception highlights the necessity of continuously cultivating empathy.

This lived experience hopes to illustrate that empathy is not optional. It is fundamental to responsible practice, demanding continuous recalibration of one’s actions based on subtle verbal and non-verbal feedback loops — a concept central to relational theories of pedagogy (Jordan & McDaniel, 2014).

Focusing on the present

In Aikido, techniques are often pre-announced, easing the cognitive load for beginners (Sweller, 1988). However, this structure can inadvertently foster anticipatory behavior, where learners rush mentally toward the outcome, disengaging from the present unfolding.

Premature ukemi (falling too early) or mental rushing disrupts the attentional presence crucial to both technical integrity and relational responsiveness. On the contrary, goal fixation can impede task performance (Norman & Shallice, 1986) and thus, focusing on performing a very impressive throw can lead to a failure in setting up the technical prerequisites to its execution, such as distance, timing, kuzushi, or levers.

Countering these tendencies requires cultivating presence-centered awareness — or zanshin — a sustained mindfulness of the evolving situation. This approach aligns with Langer’s (1989) theory of mindfulness-based learning, which emphasizes openness, curiosity, and attunement to novelty rather than rigid expectations. This approach, rooted in the understanding that reality is constantly changing, involves paying attention to both big and subtle changes, both internally and externally, to remain grounded in the present. By consciously noticing new things and making fresh distinctions, individuals stay engaged with the current situation and become more aware of the context and perspective of their actions.

Embracing Uncertainty and Failure

Aikido, despite its sophisticated body mechanics, accepts failure as an essential part of learning. In such a growth mindset (Dweck, 2006), errors are reinterpreted as opportunities for neuroplastic and relational growth rather than as personal shortcomings.

In a dōjō aligned with these principles, failure is normalized. Learners of all levels are encouraged to take risks, explore new movement possibilities, and experiment without fear of judgment — critical features of a high-trust learning environment (Senge, 1990). Thus, the dōjō becomes a laboratory for embodied inquiry, not a stage for flawless performance.

A reflective attitude towards failure is essential, since attribution bias often leads one to assume that the cause of the failure of a technique is a reluctant or overly stiff uke. In that case, one may perceive the situation as the breaking of the tacit agreement of katageiko. In reality, causes are often internal factors, such as a misalignment of one’s central axis, an application of forces that lead to uke’s point of balance, and/or a number of internal tensions that lead to a “leakage” of power

That being said, despite the rules of practice described below, one may encounter cases where a uke is obviously reluctant to let the technique go through, especially during seminars, where practitioners from other dōjōs, and with other standards, may be present. In such cases, if one does not manage to perform one’s technique, the socio-cognitive conflict (Doise et al., 1975) that result may still be a source of learning, especially for those with higher ranks, and sometimes, learning to lose gracefully, spite of the frustration or hurt ego, is a lesson in itself.

Non-Competitive Ethos and Co-Creation of Knowledge

We postulate that Aikido’s rejection of competition resonates with socio-constructivist theories of knowledge creation (Vygotsky, 1978; Rogoff, 1990), where understanding emerges through collaborative engagement, not individual domination. Each Aikido encounter is a dialogue-in-movement, where meaning is created through dialogical interaction rather than through unilateral assertion (Bakhtin, 1981).

In practice, success is measured by the coherence, responsiveness, and fluidity of the interaction — a living testament to the relational nature of learning and mastery. As we mentioned above, the obvious critique of such a consensual approach is perhaps that it does not make sufficient use of the socio-cognitive conflict, but we will argue in a subsequent article that in spite of this favorable context of katageiko, such conflicts are indeed still present, and that they actually make for the bulk of the challenge in Aikido practice, especially at a higher level.

Parameters of the sempai/kohai relationship

Although we are teaching a Japanese martial art in Japan, we must highlight the fact that some of the parameters of the sempai/kohai relationship are quite specific to Yokohama AikiDojo and thus, they warrant explaination and must be agreed on by all, especially if they run slightly differently compared to deep-rooted previous cultural experience.

Vygotsky’s (1978) concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) — the gap between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance — is vividly embodied in Aikido training. In all dōjōs, students are guided via a pre-established scaffolding (Wood et al., 1976) that consists of increasingly complex techniques, demonstrations, corrections, and physical feedback. In Japan, this scaffolding is not the exclusive prerogative of the teacher, and it is generally expected of all sempai to take it upon themselves to guide their kohai, which leads us to argue that education in Japan can be in part considered as a socio-constructivist endeavor, in spite of numerous other aspects that remain deep-rooted in what Vincent (1994) refers to as “institutional form of schooling”.

However, Yokohama AikiDojo holds very specific expectations in regard to the role of a senpai during practice. For instance, explicit instruction is the exclusive prerogative of the dōjō instructors (shidōin and fukushidōin). While all other members, especially yūdansha are expected to offer assistance to junior members, this should not take form as verbal, nor physical direction, but rather, a soft, silent and patient ukemi that grants the junior time to experiment and execute the technique, seeing it through its completion 100% of the time.

Let us insist on this: A sempai may not use of any form of physical rearrangement or verbal feedback, unless in case of imminent risk for oneself or others.

One thus may wonder what tool a sempai has at its disposal to participate in the kohai’s learning. Aikido training is dialogical in nature: each movement invites a response, creating a continuous, physical "conversation" between practitioners. Bakhtin’s (1981) notion of dialogue as the foundation of meaning-making can be directly applied to Aikido practice, where understanding emerges through physical interaction rather than verbal explanation alone.

The junior partner should always succeed. Research has shown that learning is not only iterative, it is also socially mediated (Vygotsky & Cole, 1978). In body arts, just like in language, the importance lies not in making a perfect sentence (or technique), it lies in making a complete one (Krashen, 1987).

One should thus never, ever block a junior partner. Rather, one let them see their technique through, however how long it takes, and however imperfect it may be.

The way to make this happen is as uke, to always take ukemi to the absolute best of our ability. One’s goal should always be to ensure that one’s partner is able to do their best technique, hence one is an active participant in the success of said technique at a level of 50% between tori and uke. The role of a sempai is not to be a judge of the efficacy of the technique of a partner. This holds true regardless of the extent of the gap in hierarchical relationship.

A refusal of all forms of competition

The founder was adamant that there should be no contests or matches in Aikido. While there is indeed no formalized competition in most Aikido schools, some elements of competition – albeit hidden ones – are undeniably present in the interactions between Aikidoka, on and off the tatami. Indeed, the sheer fact of visually materializing a distinction between mūdansha and yūdansha, and awarding grades based on an ordinal scale invites comparison, and calls on deep-rooted continuous monitoring and comparison to others to navigate social hierarchies (Sapolsky, 2017).

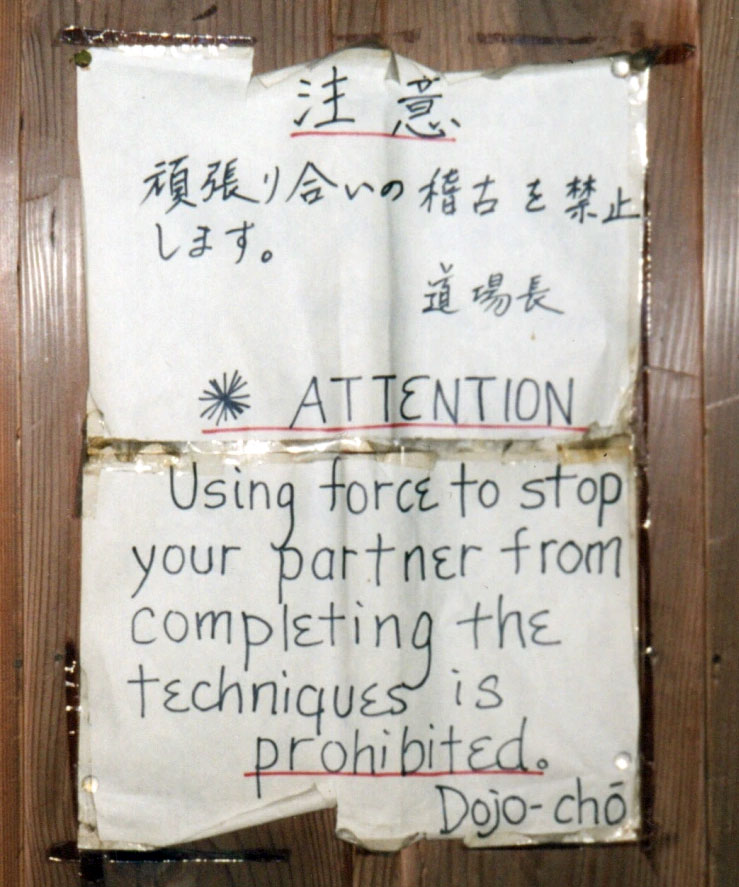

Notice written by Saito Morihiro Sensei at the Aikikai Ibaraki Branch Dojo

Notice written by Saito Morihiro Sensei at the Aikikai Ibaraki Branch Dojo

What to do and not to do during practice

The guidelines below aim to provide explicit directions on how to apply the theoretical framework described above. Any member of Yokohama AikiDojo should accept and apply those at all times. One should remember that there are many dōjōs and many ways to do Aikido, and if those guidelines are not in line with one’s conception of practice, one is encouraged to look for a dōjō that is deemed more suitable.

Role as tori

As a rule, tori is responsible for the safety of uke. Tori is thus solely responsible for the direction and timing of the throw, and hence, must only throw where and when space is available.

Half of tori’s job is to develop his own technique, but the other half is to develop the body of his partner. After an hour together, one’s partner body should be more relaxed, more flexible, and less sore than when we started, not the opposite. Pins such as nikyō are thus used as tools to progressively increase the partner’s articular amplitude through the contention. When receiving a pin, one should aim to develop one’s relaxation in the rest of one’s body, in spite of the localized tension.

As tori, one must execute a technique that falls within the ZDP (Vygotsky & Cole, 1978) of uke, never any further. That is, for example, doing a throw in a way that call on their ukemi skills, but with enough support that they can pull it out safely.

Role as uke

Aikido practice resides in the practice of a few movements with a potentially infinite number of partners, requiring one to adapt to each individual’s morphology, experience and feelings, which will often be different from ours.

Grabs and strikes

When holing the partner, the only muscle chains that should be mobilized are the intrinsic hand muscles and extrinsic muscles from the forearm. There should be no tension above the elbow, to be able to move freely in any direction, while maintaining the contact (i.e. no gap between the palm of the hand and the partner’s arm). Applying excessive prehensile strength usually causes tension in other muscular groups in the arm and shoulder, and hence make it very easy for a partner to break off the grab, or even control one’s body through the series of point of tension.

Note: This is precisely the strategy that Daito-ryu Ju-jutsu applies. One causes tensions in the body of the opponent through various levers and pressure points, and then use them to transmit force to control him.

Instead of a strong grip, one must thus keep the contact with the palm of one’s hand through the entire technique, while applying the minimum amount of finger pressure so as not to cause any pain, nor any bruising on the body of the partner. This is especially true for men practicing with children or women.

Important: The ability to gauge one’s force relative to a partner is an absolute minimum prerequisite for Aikido practice, and a person repeatedly found to be unwilling, or unable to do this will be asked to withdraw.

The grab and the pressure, whatever the intensity that is appropriate to the moment and the partner, should be held constant for as long as possible, in any directions, until the fall in unavoidable. Even then, uke and tori should maintain contact as much as possible, either in a pin or through a throw. This holds true for strikes, which even after they failed to land, will often convert in a contact with the body of the partner, in order to maintain some degree of balance and presence.

Ukemi

At the moment of the contact with the partner, one must become the best partner they have ever had. Aikido is about giving confidence to the other, not taking it away.

The ukemi should manifest itself in the constant contact with the partner, albeit with ever-changing parts of the body, one after the other, in a continuous flow.

The ukemi should never be an escape, and even on the ground the pressure must be maintained by uke on tori. Breaking this contact to take one’s own ukemi (i.e. bailing out of the technique) is an invitation to tori to take advantage of that gap and strike, and a negation of the nature of the relationship.

Conclusion

At Yokohama AikiDojo, Aikido practice is not simply about the acquisition of physical techniques — it is a holistic, relational, and deeply reflective process grounded in mutual care, embodied learning, and dialogical interaction. The pedagogical choices outlined here are all designed to create a safe, inclusive, and rigorous environment for learning and personal growth. We aim to foster not just competent martial artists, but thoughtful individuals capable of meaningful engagement with others. Ultimately, Aikido at Yokohama AikiDojo is not a path toward domination or perfection, but a shared journey toward awareness, adaptability, and the co-creation of knowledge — on and off the tatami.

References

- Bakhtin, M. M., & Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: four essays (M. Holquist & C. Emerson, Eds.; M. Holquist & C. Emerson, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

- Bennett, A. (Ed.). (2014). Budo Perspectives. Bunkasha International.

- Bernstein, N. (1967). The Co-ordination and Regulation of Movements. Pergamon Press.

- Bruner, J. S. (1974). Toward a Theory of Instruction. Belknap Press.

- Decety, J., & Jackson, P. L. (2004). The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev., 3(2), 71-100.

- Doise, W., Mugny, G., & Perret-Clermont, A. N. (1975). Social interaction and the development of cognitive operations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 5(3), 367–383.

- Dweck, C. S. (2007). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House Publishing Group.

- Fuchs, T. (2016). Embodied Knowledge – Embodied Memory. In S. Rinofner-Kreid & H. A. Wiltsche (Eds.), Analytic and Continental Philosophy: Methods and Perspectives. Proceedings of the 37th International Wittgenstein Symposium (pp. 215-230). De Gruyter.

- Gallagher, S. (2005). How the Body Shapes the Mind. Clarendon Press.

- Gentile, A. M. (1972). A Working Model of Skill Acquisition with Application to Teaching. Quest, 17(1), 3–23.

- Jordan, M. E., & McDaniel, R. R. (2014). Managing uncertainty during collaborative problem solving in elementary school teams: The role of peer influence in robotics engineering activity. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23(4), 490–536.

- Krashen, S. D. (1987). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon Press.

- Langer, E. J. (2014). Mindfulness, 25th Anniversary Edition. Hachette Books.

- Råman, J. (2018). The Organization of Transitions between Observing and Teaching in the Budo Class. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 19(1), 5.

- Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in Thinking: Cognitive Development in Social Context. Oxford University Press.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2017). Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin Publishing Group.

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization. Crown.

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2011). The Primacy of Movement. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

- Tronick, E. (2007). The Neurobehavioral and Social-emotional Development of Infants and Children. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press.

- Vincent, G. (Ed.). (1994). L'éducation prisonnière de la forme scolaire? scolarisation et socialisation dans les sociétés industrielles. Presses universitaires de Lyon.

- Vygotsky, L. S., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard university press.

- Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the Mind: Sociocultural Approach to Mediated Action. Harvard University Press.

- Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 17(2), 89–100.